Suicide is not "Selfish" or "Cowardly": In Defense of Focusing on the Person Whose Life is at Stake

Disclaimer

I don’t normally open my writing with content warnings, even when I touch on sensitive topics, but this might be one of the most sensitive pieces I’ve ever posted. Given this, I want to disclaim in advance that this post deals extensively with the topic of suicide, as the title suggests. If this is something you are uncomfortable or unsafe reading about for any reason, you might want to skip this one. That said, most of the discussion is fairly abstract. I touch on very little of the concrete feelings and motivations behind suicide, and mostly use contrived edge cases as examples 1. In this way, there is some distance from the aspects of this topic that might be the biggest problem for people.

I also focus, in this article, on problems with one type of argument against suicide that I really dislike. In general, my views on suicide are more liberal than average, and I am very suspicious that the way our mental health institutions approach suicide is kind of broken. That the people killed by it are largely invisible while those saved are highly visible. However, all this said, I think that suicide is almost never the right option, and want to open by strongly discouraging readers from taking this piece as an endorsement of the decision. If you have suicidal tendencies, please, please get help in some way. If you are comfortable with it, many countries have a suicide hotline. The US number is just 988, and they can connect you with resources relevant to your situation and needs. If you are holding off from contacting them because of fear of being involuntarily institutionalized, please find some work around, for instance hiding your IP address in some way while contacting the relevant organization 2, and give it a try anyway. Even calling from your normal phone might not be that risky; I’ve consulted an anonymous psychiatrist who told me that so long as you leave your residence for a few hours, it is unlikely there will be some extensive followup or manhunt. If 988 calls the police, they’ll check in, find no one home, and move on. This isn’t a recommendation against institutionalization, from my own experience and that of others it can often be helpful, and it’s worth familiarizing yourself with how these institutions work and considering if it makes sense for you to go to one voluntarily. Once again, this is just to say that if you are so averse to the risk of involuntary institutionalization that you are avoiding getting help at all, there are workarounds that aren’t that difficult, and I strongly recommend you try something. Your life is at stake after all.

If you have stuck with me through that lengthy disclaimer, what follows is a lightly edited version of a final paper I wrote for one of my bioethics classes. I figured, given my degree, it might be fitting to share more pieces on bioethics topics. End of life is a classic one, and one of my bigger interests in the field, outside of standard Effective Altruist topics. My take here is fairly modest, but one that I feel strongly about: those people saying that suicide is “selfish” or “cowardly” are wrong. I see people broadly agreeing with me on this more often these days, which is something of a relief, but in basically every case the justification is “because the suicidal are mentally ill and so aren’t responsible”. This is often true and adds insult to injury, but it does not exhaust the extent to which the “selfish” and “cowardly” charge is unfounded, and I’m suspicious that the assumption is often based on a basically circular view of decisional capacity sloppily conflated in the popular imagination with the broader topic of mental illness. Preventing suicide with force is coercive, tragic. It isn’t just like restraining someone about to walk off a cliff they don’t know is there, and discussing the topic with the seriousness it deserves means that “they are mentally ill and so not responsible” is suspiciously simplifying. I hope that the case I lay out here gives a good sense of why I think that, aside from moral agency considerations, blaming people for being selfish or cowardly when they want to kill themselves is just focusing on the wrong thing. I also hope I provide the appropriate amount of nuance and concession. So without further ado:

Suicide is not “Selfish” or “Cowardly”

The argument that suicide is wrong because it harms loved ones, that it is for instance “cowardly” or “selfish”, is deeply concerning to me. I have seen a sentiment like this appear many times in popular discourse (I’m told it isn’t widely believed among ethicists), but I think its core implicit arguments are fatally flawed, and deserve some more rigorous interaction than I have seen them receive. There are some ways of spelling the charge out that will work in certain cases and on certain views, but it cannot bear much weight in typical cases. If someone must continue living for their own sake, this will generally be more important than the sakes of others, and if they have good reason not to continue living for their own sakes, this will usually override the interests others have against their deaths. If this is correct, the accusation itself, ironically, may more often deserve the “selfishness” label.

The most difficult factor in the ethics of suicide, which most of the issue should actually come down to, is the topic of how someone’s own interests and choices will measure up. This will depend on several factors. For instance it will depend on how often dying can be in someone’s self-interest, how often this interest lines up with a person’s actual intention to commit suicide, and under what circumstances someone may be prevented from suicide if it is not in their best interest.

My own position on this question is that, while someone can be well within their rights to commit suicide, the choice is risky enough that proper legal and psychological evaluations would be best under ideal circumstances. For practical reasons, even this might be a barrier that often does a good deal of harm, and although I don’t have a great idea of what specifically should replace it, it seems like we should be significantly less drawn to coercive prevention on the margins. Defending this conclusion is beyond the scope of this paper however, and you may grant the thesis of this paper while accepting a very different conclusion on policy.

Another question related to the ethics of suicide is whether, regardless of whether it can be wrong to commit suicide because of the interests of others, it can be appropriate to personally choose not to commit suicide for the sake of others. The arguments towards the end of this paper may seem to imply that we should answer this question in the negative, but I deny this. I think that it can be perfectly appropriate to choose not to commit suicide because of concern for the wellbeing of others. Arguing this too, however, is beyond the scope of my paper, and you may grant my thesis while disagreeing with my answer to this question.

The first question to approach, when asking about the ethics of suicide as it relates to hurting loved ones, is where this harm comes from. There are two main candidates here. One is the harm you inflict through grief, and the other is the deprivation you inflict by leaving someone forever. Both of these accounts are vulnerable when you compare them to other cases.

A serious problem for the grief concern is that everyone dies exactly once. By inflicting your death on your current loved ones, you are sparing future loved ones this same grief. A possible counter to this is simply to deny the equivalence. Yes we are sparing future loved ones the death we are inflicting on present loved ones, but our future loved ones will have grieved less than our present ones. For some reasons that are to be expected in even the best case scenario, which I will discuss later, as well as some more depressing reasons about greater social isolation of the elderly, I think this may be true in most cases of suicide. As time passes, one’s death usually inflicts less grief, therefore committing suicide, which ensures one dies earlier, will usually inflict greater grief overall.

Even if this is a consideration however, I do not buy that most people would find it very strong in other contexts. I have said that everyone dies once, but what if someone was resurrected? Consider Lazarus rising from his tomb, and one of Jesus’ apostles lamenting “well great, now Lazarus’ death shall be inflicted on his loved ones twice”. Now of course, we also believe that great good would come from Lazarus continuing to live, but if we are glad about this for his sake, then it seems as though at least here we are willing to prioritize the interest of Lazarus in his state of living over the interest of his loved ones in not grieving. Maybe this does not deflate the objection sufficiently, if one believes that there’s a serious asymmetry in the moral relevance of an interest in life versus an interest in death, but then alter the degree of Lazarus’ interest in life. What if Lazarus would only live a few minutes before dying again, or live many years of a boring, barely-worth-living life? I contend that most still wouldn’t even think about the added grief as a factor in how good or bad his resurrection was.

Another case that is similarly undermining is of someone who, contrary to the usual state of affairs, fully expects their death to cause more grief at the age they would die by default than it will now - perhaps a charismatic orphan with no friends, who has strong prospects of eventually getting a family and friends in the future. I do not think the defender of the grief concern is committed to saying that such an orphan ought to commit suicide, but at the very least they seem committed, if they think the interests of others are a very weighty consideration in the ethics of suicide, to saying that their suicide would be far less bad than a normal suicide. I think to most people this will seem very wrong.

The other consideration, that of deprivation, fares no better. On this view, the real harm is something like all of your loved ones missing you. Arguably this may be a more serious harm because, unlike with grief, the difference between it and the default is the deprivation of the entire period one would have otherwise lived. A case in which this factor may in fact be weaker if one does not commit suicide is unimaginable.

Once again case comparisons cast doubt on whether we take considerations like this seriously in other contexts however. If I move away from home forever, and never write back, I deprive my previous loved ones of my company. Making a break like this too cleanly seems like it would at the very least be seen as inconsiderate, but this is only because we in principle could communicate and visit. If it is for our own good that we move away and never write back, perhaps we emigrate from an impoverished country with poor communication infrastructure to somewhere we can live a better life, the necessity of a clean break is more imaginable. I believe we would, once again, be judged on this decision primarily based on whether we made the right choice for ourself.

But then maybe if we survive in this new country, the deprivation of past relationships is compensated by entering new relationships. There is an impersonal sense in which you at least don’t deprive the world of friendship. I reject this counter for two reasons. One is that even if you modify the thought experiment it doesn’t seem as though our concern shifts to one’s social harm. If you move to the new country and fail to make any friends, no one thinks about how in making this move you have entirely deprived the world of your friendship. Once again, the intuitive reaction is entirely concerned with whether the immigrant is badly off in this friendless new life.

The second reason I reject this is, so long as we are viewing the deprivation on this impersonal level, that individual people don’t contribute much to per-capita friendship. Consider a world with a few hundred people in it, versus our current world. These few hundred people are deprived of about 99.9999999% of possible friendships relative to our world, and yet it seems strange to say that the people in the few hundred people world would be likely to be much more friendless than people in our current world. The absence of one person from the world does not do much to reduce the number of friends the average person actually has because social connections do not work that way, so the idea simply doesn’t pan out.

While I think each of these examples is compelling to a deontological or commonsense morality sensibility, it might be thought that consequentialists will be more bullet-biting. While some of my arguments, such as the consideration of the deprivation of friendship from the world, seem to apply to consequentialist concerns, others highlight cases in which our intuitions entirely neglect the relevance of certain sources of harm in a way a consequentialist should consider unacceptable. That said, in most of these cases, it is simply hard to see how the interests of anyone, even the strong interests, will hold up next to the interests someone has in life or death. If we would consider it strange to think a consequentialist could think killing someone against their interests would be worth it for similar benefits (removing some marginal grief equal to the difference between grief now and grief later, cutting off one valuable relationship someone has), then the only possible explanation for how this could be different in the case of suicide is if in fact no one can have as strong an interest in dying as living.

My view is that if someone can be in a bad enough situation that it is worth dying, it is hardly a stretch of the imagination that it wouldn’t stop right on the boundary of just barely not worth living. A life is a rather large thing to cut off. The problem remains, that the focus of analysis should be on the suicidal person, on the idea that it is unlikely that death is in their interests, not that even if it were in their interest, this interest would be weak. And this can ground at least many of the mentioned intuitions (perhaps the version of Lazarus who is resurrected into a short or boring life is in trouble, though).

Another interesting point for the consequentialist is that if they think that someone suffering on their deathbed should be allowed to be euthanized for their own sake, with little regard for the complaints of their loved ones (which it is my experience most consequentialists already believe), then the case for disregarding the interests of others against a suicide in the middle of someone’s life is usually even stronger. As mentioned, a life is a rather large thing to normally cut off. If a life is bad for someone when there is a great deal of it left, this net negative is statistically likely to be larger than the net negative of a shorter life. The grief argument is therefore even stronger relative to the interests of someone near the end of their life than someone near the middle. The deprivation arguments are weaker, but seem less relevant to the consequentialist in general, for reasons I just covered. If the interests of others in someone’s continued life rarely outweigh the interests of someone hoping to be euthanized near the end of their life, then the interests of others in someone’s continued life should almost never outweigh the interests of someone considering suicide near the middle of their life.

Even considering the arguments I have just made, there are some specific types of cases that might be exceptional enough to resist these problems. One is contractual obligations, another is current dependents, and yet another is living parents. Contractual obligations are one of the most obvious cases where someone might oppose suicide because of others. If you have a moral theory on which long-term contracts are valid, and on which breaking them is wrong, suicide would be a way of breaking with this contractual obligation. Still, “your death is a breach of contract” seems like an epically cold argument to elevate in this context for all but the very most serious cases of obligation.

This whole class of argument is also not clearly applicable to, say, consequentialists. Many consequentialists have expressed skepticism at the validity of long-term contracts. William Godwin famously distrusted them in the context of marriage, John Stuart Mill distrusted their validity in extreme contexts like slavery in “On Liberty”, Derek Parfit argued for the irrationality of our preference for near-term rather than long-term welfare, and Amanda Askell more recently argued against intuitions in favor of bounded utility functions based on the injustice of this same time preference. It turns out the “separateness of persons” critique goes both ways, and the consequentialist perspective has often in turn been suspicious of the moral coherence of persons. Long-term contracts may, nevertheless, be worthwhile according to consequentialists, as the only way for many important things to get done, and so one could argue that allowing people to have the out of suicide would decrease peoples’ willingness to create these useful contracts to begin with. While consequentialists might be willing to forgive long-term contracts in many cases however, those contracts that will be in more danger from suicide in particular are those that are likely to actually drive people to suicide. I don’t think it’s any stretch of the imagination to think that the world would be improved if people had less incentive to create long-term contracts that regularly drove people to suicide.

The second type of case is much more challenging, that is having a child currently depending on you as a guardian. This is, indeed, the key exception Shelley Kagan brings up when discussing the ethics of suicide and harm to others. While he did not linger on the different forms an argument from the harm to others might take, he allowed that in cases such as having a current dependent, the interests of others would likely be a dominant factor in the ethics of suicide, even though the person dying will almost certainly have the strongest stake in the event. Indeed both the view attracted to contractual obligations and the consequentialist view can find something compelling in this case. If you are the guardian of a child, you have an obligation to this child that entails remaining alive. Furthermore, this contractual obligation seems sufficiently weighty that it no longer has the cold tinge of “your death is a breach of contract”. The consequentialist meanwhile is facing a situation in which their decision can have a profound, lifelong impact on someone with even more life left than the person contemplating death. It is extremely plausible that the child’s interests in one’s suicide will be at least on par with whatever personal self-interest considerations apply.

One possible mitigating factor is that someone who is that suicidal probably shouldn’t retain guardianship anyway. It is coherent to say that a guardian should not commit suicide, but if they are at serious risk of it, they ought to stop being a guardian, and once they are not a guardian, they no longer have this decisive altruistic reason against suicide. This is limited in practice to the point where I think it is a nearly irrelevant objection. It is not so easy to just give up guardianship of one’s child, either practically or emotionally, and the difference between someone seriously at risk of suicide and someone who isn’t may be too hard to determine either from the inside or the outside for people to act on it, even if it was easier. Beyond that it is not clear that the suicide of a former guardian would be harmless to a child in most cases either - it could be nearly as emotionally traumatic if less materially threatening. Given this, guardianship could be a genuinely important exception. This, however, will only be applicable in a relatively small portion of suicides.

The final consideration is living parents. Since most people have living parents for most of their lives, but most people die after their parents, this could be a factor that actually did, in most cases, lead to suicide being wrong largely because of the interests of someone else. One difference between the grief that will be caused by suicide and the grief that will be caused in a default death is usually going to be that parents have to grieve for their dead child. This is also compelling because, from speaking with parents, it is my impression that they would often be utterly devastated by this death, maybe even caused more direct grief than anyone else one stands in relation to. There is some repugnance to this factor as well, think once more of the suicidal orphan, and I think most commonsense morality should reject this factor as decisive.

Once more however, this dismissal will be too quick for the consequentialist. A consequentialist ought never to dismiss the moral relevance of suffering, especially suffering as great as this. That said, I am ultimately not convinced that this can be as decisive a factor as the guardianship example. The dependent, after all, will generally have more life left than the guardian, and this applies both to the plausibility of a dependent’s interest having more weight than the suicidal guardian, and to the plausibility of the suicidal person’s interest having more weight than their parent. Less of their life is impacted. Once again it comes down to this, if it is really in someone’s interest to die, the interest of their guardian in their living is unlikely to outweigh it, and if it is in their interest to live, then that, and not the interests of the guardian, is what most grounds the judgment that they shouldn’t die.

Even if this holds up, it may be that a live parent is a strong enough factor that it will put the other, lesser differences in grief, over the top, and successfully weigh against the life or death interest of the suicidal person. This, I think, is one of the strongest arguments appealing to the interests of others that a consequentialist could muster against suicide. I remain skeptical that it is enough, given the smallness of the other factors (difference between griefs at a later versus earlier time, plus deprivation of one relationship that plausibly doesn’t reduce the overall number of positive relationships in the world in even the medium-term). It still seems to me that the consequentialist could mainly defend the impermissibility of suicide for someone who is currently a guardian.

But the deontologist is not entirely defeated on some of these arguments. While I do not think the deontologist could accept the argument from deprived relationships very easily, the objections I have discussed to the grief argument might be weakened by an appeal to the classic deontological side-constraints. The types of constraints, applied in the somewhat different context of assisted suicide, that were discussed by Judith Jarvis Thomson in “Physician-Assisted Suicide: Two Moral Arguments”. The first is the difference between killing and allowing to die. The deontologist might argue that it is inappropriate to compare one’s death later to one’s death now, because one’s default death would be entirely a death by inaction, whereas one’s death now would be entirely a death by action. Therefore, you should be viewed as responsible for the entire harm of your death now, not the difference in harm from a later death. The charismatic orphan example seems to give the deontologist some trouble here as well, after all the charismatic orphan still brings about a much smaller harm through their action than most people would, so shouldn’t their suicide be viewed much differently? But here I can imagine the stubborn act/omission defender saying that by far the greatest part of the wrong is in its mediation through an act, so the actual difference in the harm enacted is not reduced very much if the grief is smaller. Any grief that is brought about by an act would be enough. When you get rid of this comparative aspect however, and lean heavily on act/omission, strange things appear to happen.

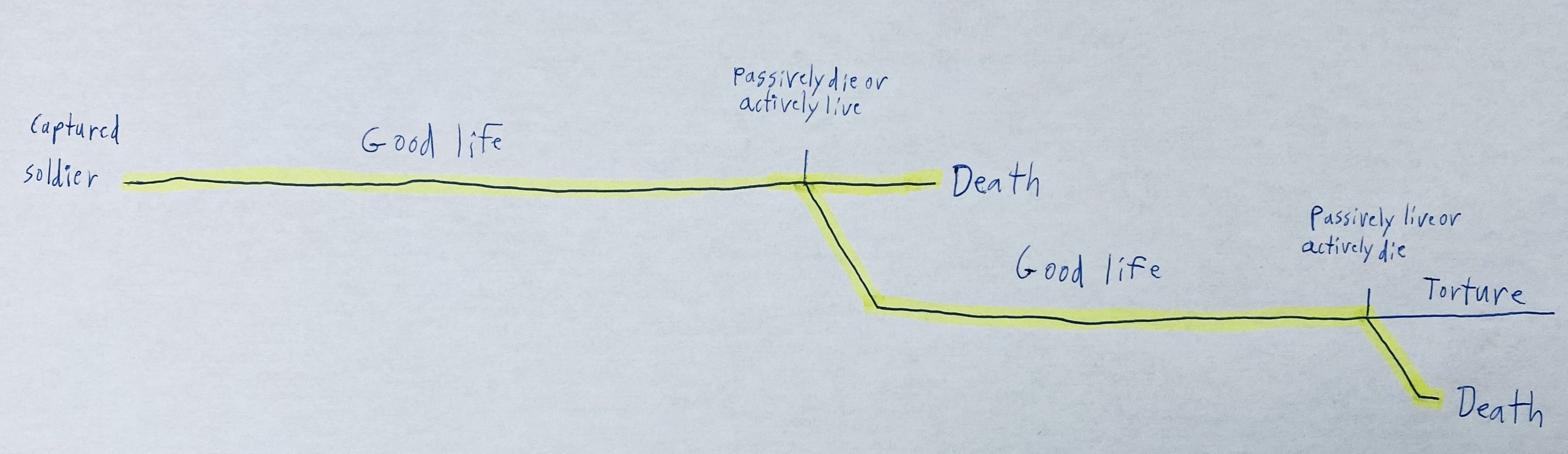

Consider being a prisoner of war 3: You have been captured by the enemy and have no hope of escape. You will, over the course of the remaining weeks, be transported to the enemy camp, where you will be tortured. You know that the torturer is a spy for your side, and if you at any point ask to be put out of your misery, he will leave you with a poison tablet. Furthermore, you are sure that you will, before long, ask to be put out of your misery once the torture starts. You fully expect your suicide, but the weeks in the meantime are good, you are even looking forward to the time you will have to live through some last sunsets and sunrises, conversations with other captured comrades, and quiet moments to reflect on your life before the end. But then the entourage gets caught in the crossfire of a battle. If you duck down, you will survive, and get the chance to live these coming weeks out, but you could also hesitate, remain standing. Then you will quickly be shot down and die. Or maybe instead you consider the possibility of refusing food and water, and so dying. Both of these would be deaths by omission. You can cut off a sizable chunk of life you wish to live, in the service of others who would be no better off for it, since the only difference is that their grief would come by omission rather than act. No one benefits, and yet you get the better scorecard, for you don’t die by suicide. How ought you act?

|

|---|

| During editing, Nick told me this thought experiment might be complicated enough that a diagram would help. Hopefully this one will help keep track of things a bit. The blue pen lines represent routes the soldier has the power to go down, the yellow highlighted paths are the ones the soldier realistically, predictably might go down. Each branch represents a choice point, with the straight paths representing omissions and the offshooting ones representing acts. Observe that the highlighted path starting from the first offshoot results in an active death, while the straight highlighted path results in a passive death. There is no highlighted, realistic path to survival; the difference in the two highlighted paths is the reverse of a usual case of suicide, in that the active death involves a later death, while the passive death results in the sooner death. This is the key strain I am trying to put on the act/omission account of suicide with this thought experiment. I am, looking back, more skeptical of this thought experiment than when I originally wrote it into my paper, and although I am leaving it in (and I ultimately think the act/omission account fails for at least the reason that the passive death really does seem relevantly like a suicide), I might try to challenge and walk back parts of it if I ever do an appendix post. |

There are still two powerful moves the deontologist appealing to act/omission could make to weaken the force of this argument. One thing they could say is that they are deontologists goddammit, not consequentialists! Yes they get the worse scorecard for the longer life than the death by omission, but a real deontologist knows that their decisions in the moment should not be responsive to what their overall moral scorecard will wind up being. I allow this, though the worse scorecard can be a repugnant feature even if it does not imply that you actually ought to duck down from the crossfire.

The other possibility is more appealing, but goes some way towards conceding the importance of one’s own interests. In each of these types of cases, someone can omit to prevent their suicide because they know they will wind up in a situation where their suicide is inevitable. Perhaps every situation where suicide is so likely that one can act on a prediction of it in advance is one in which someone is let off the hook for killing themself. This apparently solves the issue by injecting some cost/benefit analysis into it, and forgiving people for a suicide that is sufficiently understandable. The trouble is I have already discussed in the previous sections why straightforwardly weighing these harms up when we allow ourselves to compare them makes it look like the interests of the person contemplating suicide will usually be decisive. A solution of this flavor only seems to admit the most serious cases of harm to oneself, but opens up the discussion to the question of how one draws the line such that the harm to others is not morally decisive, but still grounds judgments even in cases where the person contemplating suicide is the most interested party. Indeed, even in cases like the charismatic orphan, where this harm to others is much much smaller than usual.

Both of these solutions pay at least some cost, but do something to help explain why one does not do better by this much earlier death by omission that helps no one. What neither of them explain, however, is maybe the most serious problem these cases bring up for the act/omission account. That is, it sure seems like the person hoping to die from omission is committing suicide, and that whatever we say is wrong with suicide, ought to apply to them at least as much as it would to their later deaths they expect to be caused through an act. I think this is very intuitive, but, as Thomson’s piece indicates, there are lots of people, and even laws, that bite this bullet, and suggest that death by omission through disconnected life-support or self-starving are not suicide, and that they are morally preferable to a later, acted death that will leave someone with more life and kill someone more painlessly. Thomson goes some way to spar with people who hold this view in her piece, but I won’t bother here. If you hold that this position is sensible, and are unpersuaded by Thomson, I will simply allow you to be unpersuaded by me.

But if you are convinced that something intuitively wrong with the POW case is our inability to view it as, morally, a suicide, then it seems you will need a different account. The second constraint Thomson considers in her article is intention. I believe as a definition for suicide this more promising, if we wish to know whether someone committed suicide, it seems to me that we wish to know whether they chose the way they did with the intention of dying sooner. It is too offtrack of my paper to defend this as a definition for suicide, but at the very least it would solve my concern with the prisoner of war case to describe suicide in this way.

The deontologist now has the opportunity to switch from an act/omission account of the wrongness of suicide to something more like double-effect. An act might be wrong, even if it serves a greater good, if something impermissible was part of the plan motivating this act. Causing the grief of one’s loved ones could be impermissible, if it is part of someone’s plan in committing suicide. Indeed, this seems like it does a surprisingly good job of capturing cases where the ethics of someone’s suicide intuitively depends a great deal on the effect this suicide has on others. An obvious one is that it seems wrong to kill oneself as a way to try to hurt someone else because of this effect on the other person. Likewise, it seems wrong to threaten to kill yourself in order to try to get someone to do what you want because of the way you impact the person you are threatening. It can also seem more permissible to kill yourself if your intention in doing so is to help someone else. This could even ground the judgment on our part that some cases of making a decision that will predictably result in one’s death are not mere suicides, such as charging into a doomed battle to buy civilians some time to escape.

This last example adds a further, more tragic dimension to the issue of suicide. Someone can wish to die for the sake of others, against the wishes of others. John Hardwig, in his article “Is There a Duty to Die?” discusses the range of cases in which someone might think that it is even one’s duty to die. He particularly focuses on an elderly parent who requires expensive medical and house care, and becomes a burden on their loved ones. Hardwig writes this in full awareness that it is a highly controversial position, even prefacing the argument with “I do not believe that I am idiosyncratic, morbid, mentally ill, or morally perverse.” Part of why we imagine this as so repugnant may have to do with the fact that, in fact, we actually do care primarily about the wellbeing of the person facing death by suicide when considering the ethics. Indeed the intuition might be compared to the aforementioned charismatic orphan, who will surely cause more grief with their default death than their current death. Even in this case when the remaining life of the parent may be short and deprived, and the cost is burdening one’s loved ones for an extended period, we still cannot give up on the overriding interests of the dier.

The other reason this is uncomfortable, however, is our suspicion that the parent will make this choice wrong. Parents care a great deal about their children, and may feel like a burden far too easily. This is all too likely to be a mistake. Family members who voluntarily take care of the parent at personal cost signal that the parent means a great deal to them after all – an objection not entirely lost on Hardwig, who merely suggests there can still be circumstances where this factor is not strong enough to be decisive. From many informal accounts I have seen, this may be a common motive for suicide: a sense that one is a burden on loved ones, and that they would be better off if you disappeared, even if it only takes a cursory reflection to realize all of your loved ones would deny this if asked point blank.

This, again, is a case where a significant problem with suicide comes from its effects on others. If you think you are more like the soldier allowing civilians to escape by charging into a doomed battle, you may be justified in dying against your own interests. On the other hand, it matters if you are trying to die for the sake of others, and it does not even help those others. Indeed this account is even persuasive when you reintroduce consequentialism. John Stuart Mill famously argued that a significant reason we shouldn’t make decisions about the lives of others is that they know their own good better than us. I might add to this the maybe even more trivial point that we have better incentives to serve our own good than that of others. Whether these two considerations are enough to undermine the paternalistic argument against suicide is out of the scope of this paper, and I think it usually does not, but what it does appear to suggest is that people who plan on sacrificing some of their own good for the sake of others are on much shakier footing. They are sacrificing a good they are sure of, with the belief that this will bring about something even better for someone they are ill-prepared to speak for, or if they are malicious, with the intention of manipulating someone else in a way that goes against their interests. This suggests that even though preventing suicide appears to involve restricting liberty, Mill’s perspective should still make us suspicious of suicide that is motivated by impacts on others.

Still, the intention argument doesn’t get you very far towards restricting suicide. For one thing, even if you managed to claim that every choice that involved the intention of one’s death was wrong, double effect could only do this by appealing to the effects on others for cases in which that impact was an intention. The grief argument would be irrelevant if, as in many if not all cases, it was merely an unfortunate side-effect. The other problem is more practical.

Thomson, in interacting with the intention objection to euthanasia, points out how strange it would be for us to try shaping our policies around what the intended effects of euthanasia were. If one doctor could only give someone a fatal dose of morphine out of the intention to kill the patient, would we have to grab another doctor who was able to only intend pain relief to administer the same fatal dose? Regulating intention seems less difficult in cases of suicide than assisted suicide at least. After all, you cannot resort to grabbing a different self who only intends to die for your own sake. There are even some of these cases we may be comfortable directly intervening in. Take the example of someone threatening suicide, it may be true that someone sneaky could just report that, as a matter of fact, they will be miserable enough to commit suicide if you don’t do what they want, without intending to directly manipulate you, but if they are public about this, it seems plausible to me that restraining this person from suicide could more plausibly be justified as a preventative against the very likely intention of manipulation, regardless of that person’s interests (there is an ancillary concern here, however, about whether given this excuse health authorities will drive a truck through it and ultimately do more harm than good).

Intention can still ground the judgment that from someone’s own perspective, they often do something wrong by dying with the intention of impacting others, but again, this is not only limited in the cases it applies to at all, but it will generally not be able to justify someone else restraining you. The intention account may also superficially seem to imply that deciding against suicide for the sake of others is inappropriate. As I mentioned earlier, I deny, but will not interact with this possibility.

What I hope this series of arguments has demonstrated is that if suicide should usually be viewed as impermissible, this either requires biting bullets that seem repugnant, or, more realistically, claiming that it is bad because of the way it is bad for the person who commits suicide. To some, this conclusion would imply that committing suicide is not an act of injustice, but at worst an act of imprudence. I deny that this must be true, for the consequentialist reasons of incoherence of persons mentioned earlier, but I think whichever way you go, accusations against a suicidal person’s character are repugnant. There is added repugnance in this judgment because people ideating suicide are often both mentally ill and miserable. Accusing someone suffering badly of being selfish is insensitive in the best of times, and even the accusation that is more fitting, that of imprudence or short-sightedness, would be repugnant and judgmental when leveled at someone who is mentally unwell. If we are to have a frank, and general conversation about the ethics of suicide, this part of the conversation deserves to be viewed with great wariness – and personally, I think it ought to mostly be abandoned in favor of accounts that prioritize a focus on the person in danger of suicide.

-

Ed. Note: This is common and appropriate. ↩︎

-

Ed. Note: For example, you can do this by using a free trial of a “VPN” service. ↩︎

-

I discussed similar points about indefinite life in an earlier post. ↩︎

If , help us write more by donating to our Patreon.

Tagged: